Mexico City’s Flea Market of Darkness – Tianguis Cultural del Chopo

Words by Andy Hume

Part weekend warrior’s Hot Topic, part beer-fed aging metalhead playland, Tianguis Cultural del Chopo is the street market source for all things musically and culturally black: metal, punk, goth, oi!, hardcore, etc. Currently situated along Calle Juan Aldama (across from the Buenavista Metro station), El Chopo began in 1980 near the Museo Universitario del Chopo as a trading post for music, literature, and film fans far on the outskirts of “normal.”

Today as you enter the market you can expect to be greeted with murmurs of “mota… cocaina… peyote…” Unless of course the cops are posted along the walkways, then it’s all legit business, (if of an often trademark-infringing sort of variety). Darketo goth/emo teens prance through, capitalizing on this, the supreme opportunity to let their purple hair float in the breeze over their black shrouded shoulders. Pierced and tattooed parents; the frightening, grisly scripts of their favorite bands scribbled in white and red across their black T-shirts; pull small children by the hand – some of the kids appearing punk/metal-curious, while others wear the soccer jerseys and embroidered Polos of the straight-laced, conventional Mexican youth.

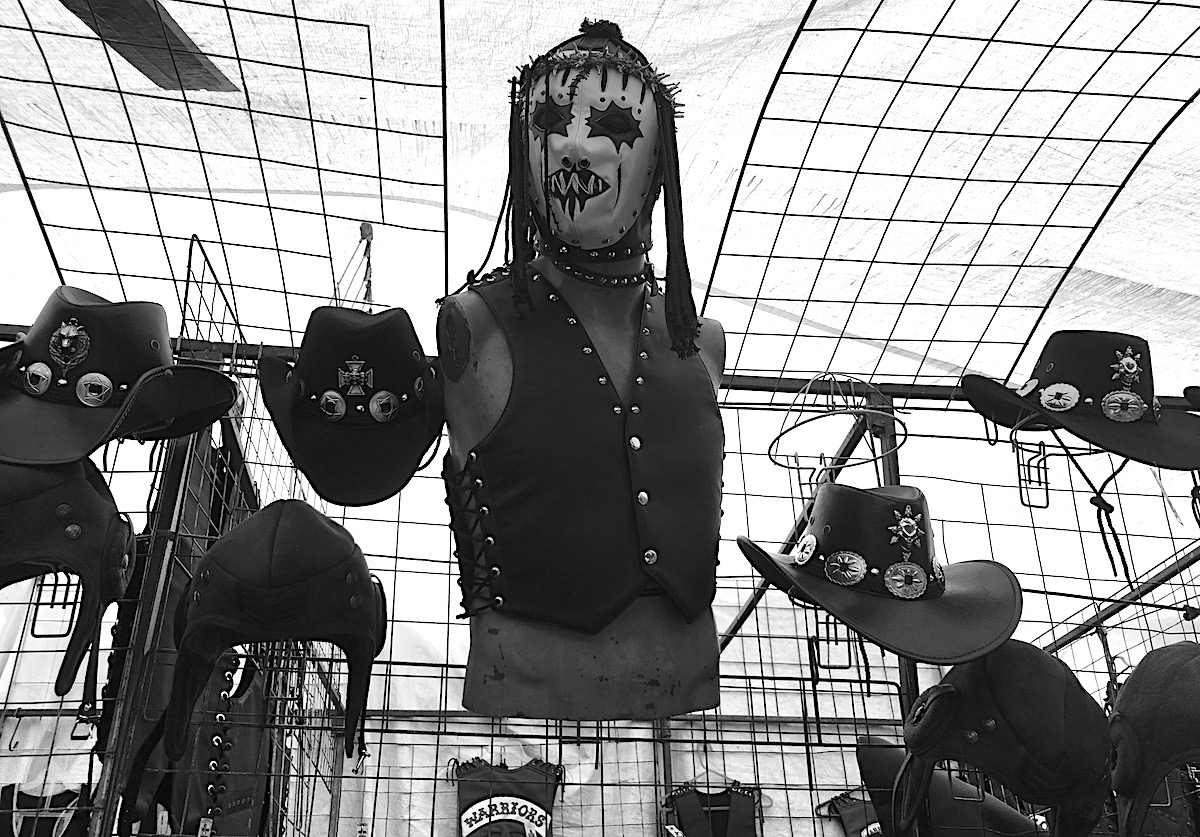

The T-shirt sellers tell me that Metallica and Joy Division are among the most popular these days, “but it’s always changing.” From my view, the most common appear to be Ramones, Slayer, Kiss, and Brujeria. And you certainly can’t throw a mesh sleeveless without hitting some kind of Misfits paraphernalia – from baby onesies to wall clocks, bongs, slip on shoes, and all manner of leathers. A skinhead with “street punk” and a set of brass knuckles tattooed on his head to prove it, gives me a somewhat menacing, “Take a look, blondie,” as I pass his stall of be-spiked and -patched sleeveless jean jackets. Sort of seems like the kind of thing you should probably make for yourself if you’re going to wear it. But I don’t say shit.

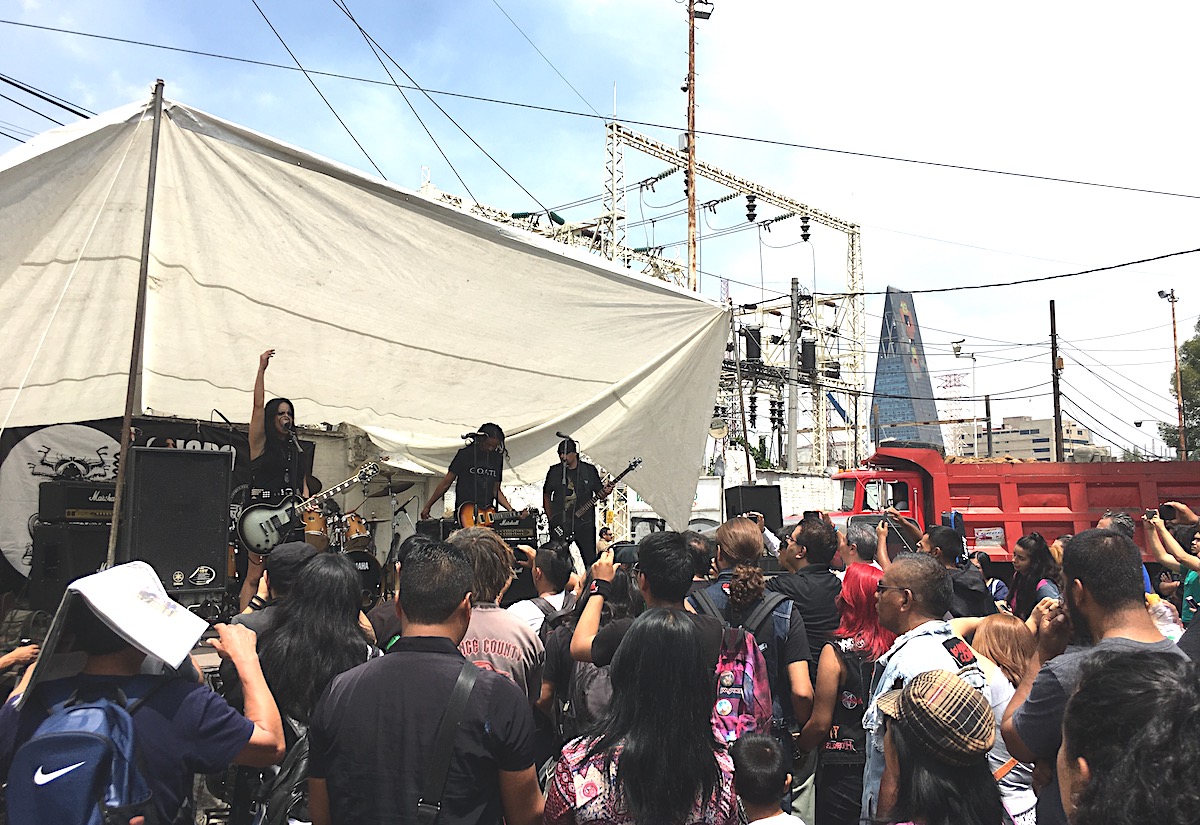

Bondage gear, knockoff skate brands, old rock mags, a surprising collection of Rick & Morty accouterments, as well as fiercely Leftist zines and very serious music collections. As I walk north toward the end of the stalls, the band T-shirts become more obscure, more threateningly heavy (and much more well made). At the end of it, the market opens up to the Radio Chopo stage (appropriately situated directly in front of an electrical substation), where almost every Saturday at 11AM begin a variety of mostly Mexican, mostly metal-inspired bands. Despite the abundance of cheese, El Chopo has been a truly big deal for the Mexican underground for a long time. It’s a hard-fought privilege to play here, and the bands are clearly psyched to be on stage.

In front of the stage is the open vinyl, cassette, and CD exchange with thousands of wildly obscure, as well as comfortably mainstream records. These are the guys that have been doing this since the beginning, the spreaders of the good word of rock. I’m here with my friend Alvaro Muñoz, member of local band, Chévere Suave. Alvaro first came to El Chopo with his older brother in the 90s: “This place was the best because you got to hang out with skaters, punks, and darketos. This is where my obsession with new and different music was born, because you could just trade stuff for CDs or skate shoes – you didn’t need any money. I wanted to become a musician because of this place and my brother.”

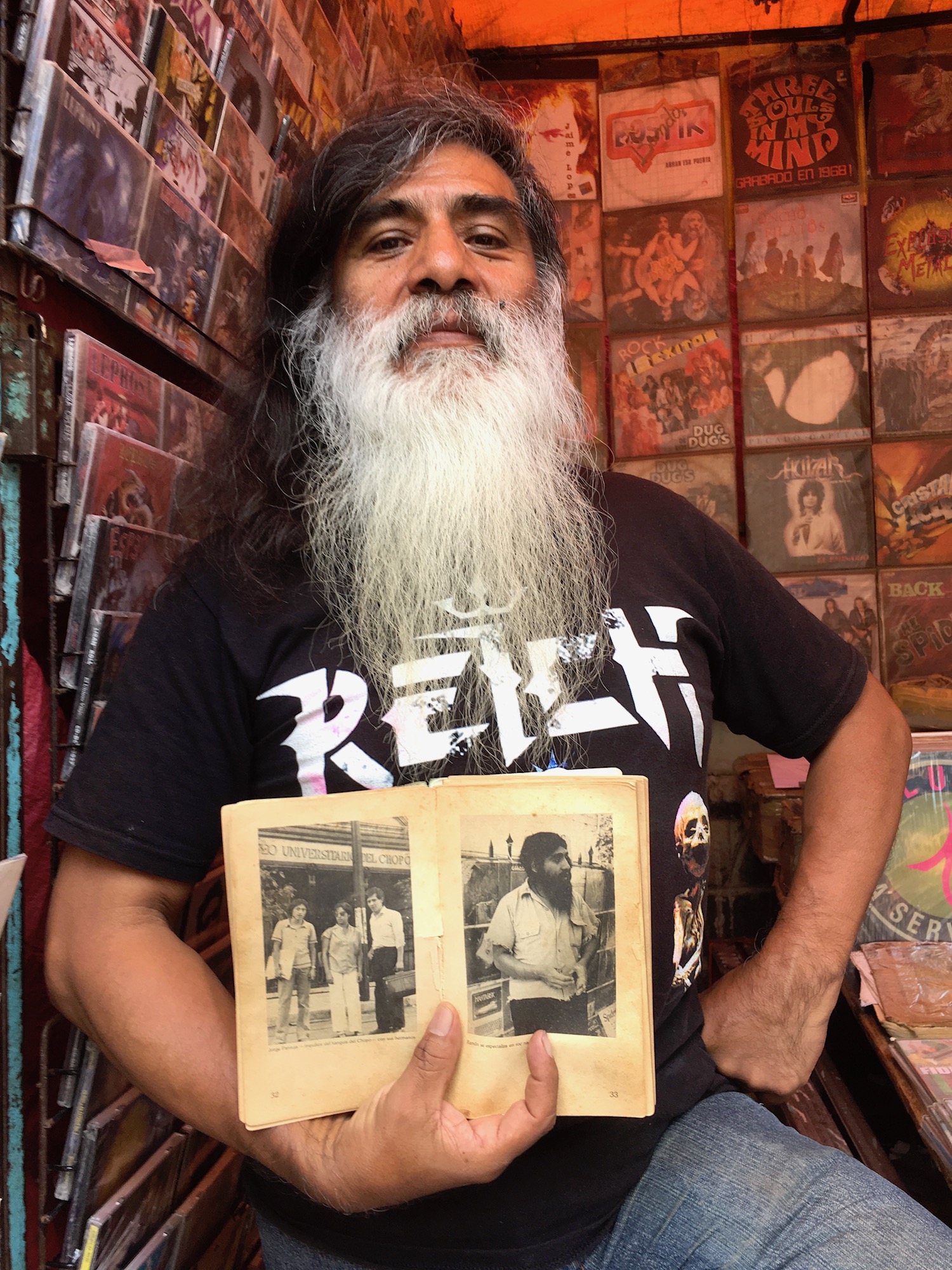

Ramón García, the architect of a beautifully silky, long grey-black beard, and one of El Chopo’s founders and most beloved personalities, has been trading and selling some of the best and hardest to find albums at El Chopo for 38 years. He specializes almost exclusively in Mexican bands, feeling they’re often overlooked, even within the country. “In Mexico, all of the infrastructure around music has always excluded the true Mexican rock,” he says. “Mexican rock has always been underground. There are no magazines that support it. There’s no television. There’s no radio. It doesn’t exist. There’s more interest in Mexican groups from the 70s and 80s in countries outside Mexico.”

To the side of the stage, under a small tarp sits the espacio anarco-punk, containing a handful of collectivos mostly of the crust-punk variety, touting causes like Antifa, the Peruvian Left, and Palestine. I speak with a punk supporting the indigenous peoples, particularly the women, of Chiapas – a collection of booklets, zines, and CDs spread below him. He’s originally from Mexico City, has been coming to El Chopo for 20 years, and now makes the trip only once a year from Chiapas. He declines to give his name but tells me that he feels separate from the rest of the market these days: “They’re selling pants and stuff out there now. When people had kids and grandkids things changed, and we were left here [in espacio anarco-punk]. But we’re still here.”

Later Alvaro and I speak more with Ramón García at his Chopo stall, where he sells and trades from his collection of over 10,000 albums from across the spectrum of Mexican rock. “[El Chopo] has changed a lot,” he tells us. “Because it’s no longer 100% for music, or literature, or cinema. And my partners didn’t have the mental fortitude to continue resisting, to keep coming up with proposals. But we still have a lot of the originals who continue to come back for what we saw in the beginning. In my case, Mexican rock. We have people still selling literature, still selling films. And that’s why the market was born.”

Ramón has been with the Mexican rock underground since its approximate inception, having attended and assisted at the great Mexican rock festival of 1971, Festival Rock y Ruedas de Avándaro. Avándaro was seen as a massive breakthrough for Mexican counterculture, by some accounts attracting 500,000 attendants. Many of the bands that played the festival had been censored by the government, banned from venues, even attacked by the police. Alvaro shares Ramón’s affinity for the festival and the era. Just months ago, he played a reunion gig with one of the festival’s most admired bands, Peace & Love.

He asks Ramón, “What happened? From what you lived through… How long after Avándaro did rock disappear?”

After a number of expletives regarding the current state of pop culture, Ramón settles on a response: “After Avándaro… Before and after Avándaro, Mexican rock is where it has always been, underground.”

Tianguis Cultural El Chopo

Saturdays 11AM – 5PM

LOCATION: https://goo.gl/maps/VpM7WFybWzs

Purists will tell you it’s on Calle Juan Aldama between Sol and Luna. But it actually starts at Mosqueta and Aldama and continues north.

![New [Unnamed] Corn Hole Opens Doors in Mexico City to Celebrate Folk Culture](http://hayo.co/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/IMG_3365-350x300.jpg)